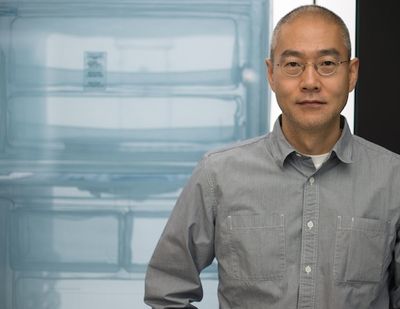

Do Ho Suh

Do Ho Suh has a lot going on. When I meet with him he has just arrived from Korea following the opening of his most ambitious project to date: the installation of his work Home Within Home Within Home Within Home Within Home at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul.

The site-specific sculpture involved the creation of two houses—a replica of his parents' home in Seoul and his own apartment in New York—both made to scale and entirely of the translucent fabric that has become his signature medium. In contrast, the exhibition that brings us together is less monumental in size, but equally intimate.

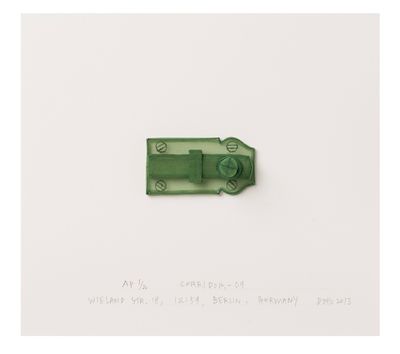

We meet on the morning his solo exhibition, Specimen Series, opens at Lehmann Maupin's Hong Kong space. Timed to coincide with the Seoul opening, the exhibition continues Suh's exploration of the idea of home and the construction of memory via architectural space. For this exhibition, the artist has reproduced, in fabric and again to scale, the objects from his former houses and apartments.

The gallery space has been carved in two: one side has been painted black and dimly lit, and the other side is painted white and well lit. In the darker section household appliances presented in glass vitrines include a pink radiator and a blue bathtub, toilet, medicine cabinet, stove, and refrigerator. The artist has lit each box, drawing out the translucent quality of the fabric, which also results in each object taking on a shimmering, jewel-like quality. The other half of the gallery presents, in small white frames of about 30 x 30cm, smaller objects from the apartment: light switches, door chains, and other such domestic details, all executed with exacting detail.

Each item in the exhibition is given a title referencing the home address to which the object relates; 'Specimen Series: 348 West 22nd Street, APT, New York, NY 10011. USA, Corridor/ First Floor 4', is written below a light switch. There is an acute contrast between the intimacy of the domestic objects shared, and their careful scientific-like cataloguing and presentation. The viewer is both invited to step into Suh's personal space, and yet kept at arm's length. The concept of home becomes both a topic for subjective contemplation, and an idea to explore objectively.

ADHans Ulrich Obrist, who has interviewed you before, is always fascinated by what he calls the 'epiphany' moment in an artist's career. About three years ago he asked you about your own epiphany moment and I was interested to re-visit your answer here?

DHSWhen Hans Ulrich asked me that question I was caught off-guard. It is such a big question. And I don't think I had one epiphany moment. I think there have been several moments. Moving from painting to sculpture was certainly one of the most important moments, but when I look back over the last couple of decades I think some important moments happened even before this. My work and what it has become can be traced back much earlier. It can be traced back to Korea and to the years before I left Korea for the United States.

ADIn what way can it be traced back? Are you referring to your investigation of space or to your use of materials?

DHSWell I think my interest in looking at how a work can be transported and the issue of site-specificity started in Korea. An interesting thing is that nobody—neither Korean nor American art historians or critics—ever ask me about the work I did before I moved to the US.

ADCould you tell me a bit about your very early work?

DHSYes. The seed for my work was planted when in Korea. I had started to make pieces that were transportable. I was thinking already about site-specificity and about context and I was questioning modernism without really knowing it. I was a student of traditional painting, so over that time I didn't really know what was going on in terms of discourse outside of Korea. My investigation came out of my own necessity, but was aligned with what was going on outside of Korea. The works I was making at the very beginning, before I moved to the US, were questioning the notion of site-specificity.

ADIn what ways were you exploring notions of site through the medium of painting?

DHSMy paintings almost literally walked out of the wall. They were almost like freestanding pieces—almost like sculpture, but with images on the surface.

I was observing the form of scroll painting and screen painting in Asian art. The main difference between scroll painting versus canvas painting in the western tradition is that the scroll painting is meant to be transported. You are meant to roll the work and then when you show the painting you unroll it. In comparison, the western painting is meant to be framed and hung on a wall.

What was significant for me when I look back at this period was the realisation that the painting didn't have to be on the wall, and that it could be moved. This was a significant departure. So I had that epiphany moment when I was in Korea.

Asian traditional painting allows for one picture to work as one piece or as several pieces. You can create one big painting by putting separate pieces together or you can have different paintings. You can fragment the work. I was also interested in this notion.

I made four large bodies of work that could work as one piece, but equally they could be seen as individual works. These works were freestanding paintings, which I suppose were really sculpture. Each facet had images and the images were fragmented. It created a kind of hypertext, and the audience could create their own image from the different fragments. It was impossible to see the entire picture because the work was so big and the painting was not only on one side. You had to walk around the work to experience it.

ADThis is very similar in concept to one of your early sculptural pieces, Some/One. In this piece, the audience is meant to approach the work from the back so that the interior of the piece, which is mirrored, is not seen until you walk around and discover your own reflection.

DHSYes that is a very good example. The piece comes down and becomes the floor and the audience is encouraged to walk on the floor. That is actually a very important aspect of my work. It was about challenging the notion of the modern sculpture—but I can talk about that later.

In relation to my work in Korea, the idea was that the sculpture actually stood out from the wall, and the audience's movement activated it. The relationship between the piece and the audience is important. The audience in painting is meant to have control insofar as the painting should be contemplated from a distance, but in this work, the audience cannot see the entire work. It was about turning the relationship between the audience and artwork upside down.

Were there any other works from these early days in Korea that influenced your trajectory?

DHSYes, I made another work where I blew up hundreds of balloons in my studio just outside of Seoul. It was a piece for a group exhibition in the centre of Seoul. My idea was to transport the breath of the artist—being the air that was captured in the balloon. These balloons were then put into a much large plastic bag, half of which was painted opaque so there was a play between transparency and opacity.

I hired a truck to transport the balloons. The work was malleable. I had two rooms in which to show the work and it was a large sack of balloons and the piece started from one gallery and followed the wall and moved into the other room. So I occupied two rooms, and again the viewer couldn't see the work. This work was both about fragmentation, making it impossible to contemplate as a whole, and it was also about transporting space.

And that was probably the last work I did before I moved to the States.

ADIt is very interesting to hear where some of the ideas evident in your work today began—those relating to the transportation of work, site-specificity, and the relationship between a work and the audience.

For many years, your work has also explored themes around the idea of home and cultural displacement. Presumably these ideas began to manifest after you left Korea for America?

DHSYes, exactly. Once I moved, my work started to emphasise the aspect of my displacement. I was also exposed to new materials, new ideas, and new techniques—this was before New York, when I was studying at Rhode Island. I started to absorb different thoughts and theories. So that was nurturing me in order to move forward. My ideas that I had in Korea were probably immature and the study in the US gave the impetus to what came afterwards.

ADNow you are very much known as a sculpture and installation artist. Can you see a re-visiting of painting?

DHSIn the last few years I have made a few paintings. Technically they are almost identical to the drawings that I have made, it's just that I did them on a canvas. With a canvas you have a certain amount of freedom to make a mess. Paper is like a one-shot deal right? The painting you can get messy. I was trained as a painter and I was surprised at how quickly it came back.

ADIt is interesting that you talk of the messiness of painting, because when I look at your work I am very aware of how precise, structured, and neat they are—like architectural drawings.

DHSThe reason I went into sculpture was because of the messiness of the painting. The sculpture involves a more structured process, and by nature you have to be more organised. You are dealing with expensive materials and if you, for example, cut the metal incorrectly—well that's it. In contrast, with a canvas you can scrape off the painting and re-paint. So the approach is so different.

I do like being organised. With painting, there are too many variables.

ADBut can we expect an exhibition of painting from you in the near future?

DHSYes. Well my next show at Lehmann Maupin in New York is a drawing show. I may have one big painting in the show. The way I am going to make that painting is going to be the same way I do the drawings.

ADCan you explain more about that technique?

DHSI made a series of drawings on paper with an airbrush and the medium was ink and lacquer paint. I am going to do that on the canvas and create a painting, but it will be messier. I was relieved that I am able to experience the possibility of being messy. For the last couple of years I have wanted to do that.

It is funny you mentioned this. Yesterday in Seoul I met up with a friend. He is an architect and a professor. He is older than me. He also had a painting exhibition. He showed me his work yesterday and I had this absolute urge to make paintings. So I think that is a good sign.

ADThe timing is interesting, because just two days ago your installation Home within Home opened to the public at the National Museum of Modern & Contemporary Art in Seoul. And this work is probably the largest and therefore most demanding fabric work you have done to date.

DHSYes by far that is probably the most complex piece I have ever made—certainly in terms of scale and technicality.

I feel very confident I have pushed the limitation of fabric and the manner of making the work to its ultimate level. I feel I can now make anything. I think if someone wanted me to make St Paul's Cathedral in London, with enough time and money, I could do it. So I want to explore something else. That doesn't mean I won't make the fabric architecture anymore. But possibly I will be more interested in scale.

I am interested in exploring the more intimate process of painting. But hey, I only just started this thinking in the last couple of days!

ADSo I won't hold you to it?

DHSNo!

ADTell me about the work Home Within Home that is showing at the MMCA in Seoul?

DHSThe full title of the work is Home within Home within Home within Home within Home. The title references five homes, but actually there are two homes in the piece. One home is my parent's home in Korea. It is the smallest one. It is the home I grew up in and when I go to Seoul that is where I stay. And then there is the larger house—the one that encapsulates the smaller home within it—and this larger home is my first American home, which I lived in when I went into the US. Both homes are made of fabric and are on 1:1 scale. The Korean house is suspended in the air and the American house is freestanding and grounded—so you can enter into the house and you can wonder around it.

The other homes referenced in the title include the Museum itself and also the site of the Museum. The site of the Museum is a historical site and it used to be a part of the Palace complex. During the Japanese occupation, the Japanese systematically tried to destroy the Korean kingdom, including the Palace. So part of the history of the complex is that after the original structure was destroyed following the Japanese occupation, they built a modern hospital on the site. But then in the 60s the hospital became a military hospital and next to it was the military intelligence headquarters, which symbolised the dictatorship during the 70s and 80s. These buildings were then turned over for the use of the Museum and during the construction of the Museum when they excavated the ground they found a lot of ruins. They had to change the design of the Museum because of that and they also recreated one of the Palace buildings. So there are many different layers.

ADYour work is often preoccupied with the issue of overlapping spaces, and related to this, the question of boundaries. Bearing this in mind, I was interested to talk about the work you have done in relation to the Gwangju Biennale.

In collaboration with Suh Architects, your brother's practice, you have created a work entitled In-Between Hotel. This I understand comprises a 'roving hotel', which is mounted on the back of a truck; and it will be parked in gaps between Gwangju homes. This appears to be perhaps the beginning of a new investigation in your practice—the exploration of in-between spaces, of the space within a boundary line. Perhaps we can talk about this work?

DHSYou are right. I think it was very much an attempt to blend the boundaries and then actually help the residents and visitors to understand and question the existence of the boundary and the blurring of that boundary. The work raises questions that include: Is there a boundary? What is a boundary? Where is the boundary?

By inserting the truck into these physical spaces, it throws up a few things.

ADThe neighbours are not legally the hosts and therefore it raises the question of who controls the public spaces we take for granted as private?

DHSRight. The tricky thing is that the lots where the Hotel is parked do not belong to the individuals living next door—the city owns this space, but psychologically the neighbours feel it is their land. So to park the Hotel, we get the permission of the neighbours; but it actually isn't an official permission that we are required to get from them. We have to negotiate with them. This type of negotiation is a balancing act, because it raises the question of where the boundaries are. Once they accept the Hotel within the boundary, then the boundary and the gap disappears. But what is really interesting is what happens to the residents after the Hotel moves on—because they have not thought about that space before and whether they actually own it or have control over it.

ADWho can stay in the Hotel?

DHSAnybody. You have to go through a normal reservation process. We created a whole system around this.

ADThe Hotel, as an architectural space, also raises questions regarding private and shared or public space, because a hotel is a shared space that people psychologically take ownership over and make their own private space for a brief period?

DHSYes, I was interested in the Hotel in this way. A hotel creates an interesting space. I have spent one third of my life in hotel rooms. It raises a question as to what is public space and what is private space? A hotel is a completely public space, in a way. Think about how many people slept on the same bed. No matter how expensive it is, a hotel room is a shared space that becomes a private space.

The Folly Project is a public art project, but someone pointed out to me the private nature of the Hotel. It was the woman who was the first person to sleep in the Hotel and I had a chance to talk to her at the opening and she said: 'Yes this is a public art piece, but when I enter it, it becomes private'. There are many Folly Projects, but for an individual involved in this particular Hotel project, it will become very personal—if they sleep there they will probably spend eight hours at least with the work. The other projects you will spend a very short time with—the work therefore becomes very personal.

ADI have noticed with the exhibition here at Lehmann Maupin that you have honed in on the details of your larger works—presented, in fact, fragments of your installations.

DHSI have separated out the various pieces that have appeared in the bigger fabric works, and by separating them out, you start to become more aware of the details within the individual elements of the bigger works. If, for example, you look at the radiator or refrigerator or stove, each item becomes its own architectural structure. It creates a small universe within the bigger piece. It is interesting that the contextualised elements from the bigger installation pieces become works in themselves.

Not directly, but obviously when I was conceiving this exhibition I was able to conceive this idea of placing just the appliances into the space because the square footage of the gallery is quite similar to my apartment in New York, so without me building the walls I can create the intimacy of a small New York apartment. The scale works here. —[O]